The Arizona Trail: Sonita to the Mexico Border

Days 31-35 // 96.3 miles // 17,030ft+

Day 31 (12/11/21): 20.8 miles & 3,400ft+

Spending a month on a trail is a gift.

It takes weeks to sink into a rhythm with the natural world, to stop fighting the environment and just relax into each day you are given.

And so, reaching the one-month-mark on the AZT felt like something to be celebrated.

Trail Magic!My 31st day on trail was filled with long breaks.

I stopped several times to sit in the middle of the trail, spreading my belongings all around me, confident no one would appear and ask me to move. I basked lazily in the warm morning sun and hid from the afternoon blaze.

I felt as though I could have finished the trail tomorrow or the next day if I pushed harder—part of me itched to—but I was excited to meet Judy the next morning and take a day off in Sahuarita.

Suddenly, I wasn’t in a rush.

I had woken up to cold, wet socks and a tent full of condensation, but after taking the time to dry everything out in the sun, the damp misery was naught but a vague memory.

As I sat eating peanut butter off my wooden spoon, I watched a herd of Coues deer bound across the hills where I’d soon be walking.

Their calls echoed across the valley between us, grey bodies leaping and dancing through the golden grass, seemingly for the enjoyment of it, a startling flash of white fanning up behind each of them.

A surprisingly delicious water source, despite its green and slimy appearance.When I packed up and continued my journey south, I ran into the hunter I’d flown past the night before.

He did a double take as I labored my way up the hill towards him.

“Did you walk here?” He asked.

“Yes, didn’t you?”

“No, I drove around. That’s a long way to walk, how many days are you out here for?”

“I’m hiking the Arizona Trail, I’ve been out here for a month now,” I told him as I paused to catch my breath, leaning on my trekking poles.

He asked me a bunch of questions about the trail, whether or not I carried a weapon, how I got food, how heavy my pack was, and I then asked him about his hunt, how long he stayed out, how often he “got” something—the conversation was a welcome diversion.

Afterwards, we said our goodbyes and I pressed on. The day was now singing with heat, and the dusty forest service roads I walked on felt oppressive.

Before I ran into the hunter, I’d been the recipient of some anonymous trail magic. A cooler full of beer, juice, water, and twinkies, had been positioned in the shade next to a gate. I bypassed the beer, in favor of an OJ and a pastry (if you can call a Twinkie that).

I felt so grateful for the “angels” who left gifts out for hikers this late in the season.

Eventually I made it to Kentucky Camp—a group of 5 adobe buildings that used to be occupied by Santa Rita Water and Mining Company in the early 1900’s—only 3 miles away from where I would meet Judy the next morning.

I made a donation in the metal pipe out front, filled my water bottles with potable water from the spigot and then sat on the porch for a while.

I took some time to organize my pack, gathering any stray pieces of trash and disposing of them in the bear-proof bins that were provided by the camp.

I killed an hour and half just sitting on the deck, staring out at the world and journaling.

Around 4:30PM, I departed for the TH where I would meet Judy; hoping to find decent camping.

When I arrived, there was plenty of flat ground, but it was all so exposed to the passing gravel road, which seemed to have a lot of traffic so late in the day.

I dawdled for a while, stalling. I didn’t want to set up my tent and then get told to move by a passerby.

Around 6PM, I finally chose my spot and began building my house. It was going to get cold here, in this low swath of land, I just knew it.

Day 32 (12/12/21): Zero Day with Judy

Sure enough, the next morning I woke to a thick layer of frost inside my tent, frozen water bottles AND frozen shoes. I’d made the silly mistake of leaving my trailrunners outside my tent and they were now coated in what appeared to be a fine layer of snow.

I was grossed out by the icey-cold wetness of the items surrounding me in my tent, and extricated myself as quickly as possible. My sore body struggled out of the hobbit door, as I forced it to fold in ways it simply couldn’t after nearly 700 miles of walking.

I packed my backpack sloppily, knowing I would have a chance to dry everything out at Judy’s, shook the ice out of my tent, and begrudgingly slipped on my frozen shoes.

I found a sliver of sunlight in the parking lot and spread my Z-lite foam sleeping-pad out on the gravel. I was puffy faced and chilly, stuffing Love Crunch granola into my mouth by the handful.

Frost covering my tentThe frost after shaking out my tentI heard the crunching of tires on the road, it was an hour before Judy was supposed to arrive, but hope swelled within me.

I saw a silver pick-up pulling into the parking lot—it had to be her!

And it was.

I scrambled to gather my things as we greeted each other. She had brought me a thermos of coffee.

Moments like those are meant to be savored. It isn’t everyday that you spend a cold night in a parking lot, only to be greeted by friendly face, a hot cup of coffee, and a ride into town.

And besides, Judy barely knew me. We’d met one morning at a motel in Flagstaff—hundreds of miles ago—there, she’d offered to pick me up for a zero day when I got closer to the border.

She’d backpacked portions of the Appalachian Trail with her sons in years past, and was familiar with thru-hiking. She wanted to help.

Her generosity was such a gift. I spent the day showering, resupplying, eating good food and participating in great conversation.

Making connections is what life is all about, it’s what hiking is all about. I go out into the mountains to find myself, and I find myself, alone, in nature as much as I do through the interactions I have with the people I encounter.

“The land knows you, even when you are lost” —Braiding Sweetgrass, by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Day 33 (12/13/21): 31 miles & 3,700ft+

Judy brought me back to the trail at 8AM, we said our goodbyes and parted ways as good friends.

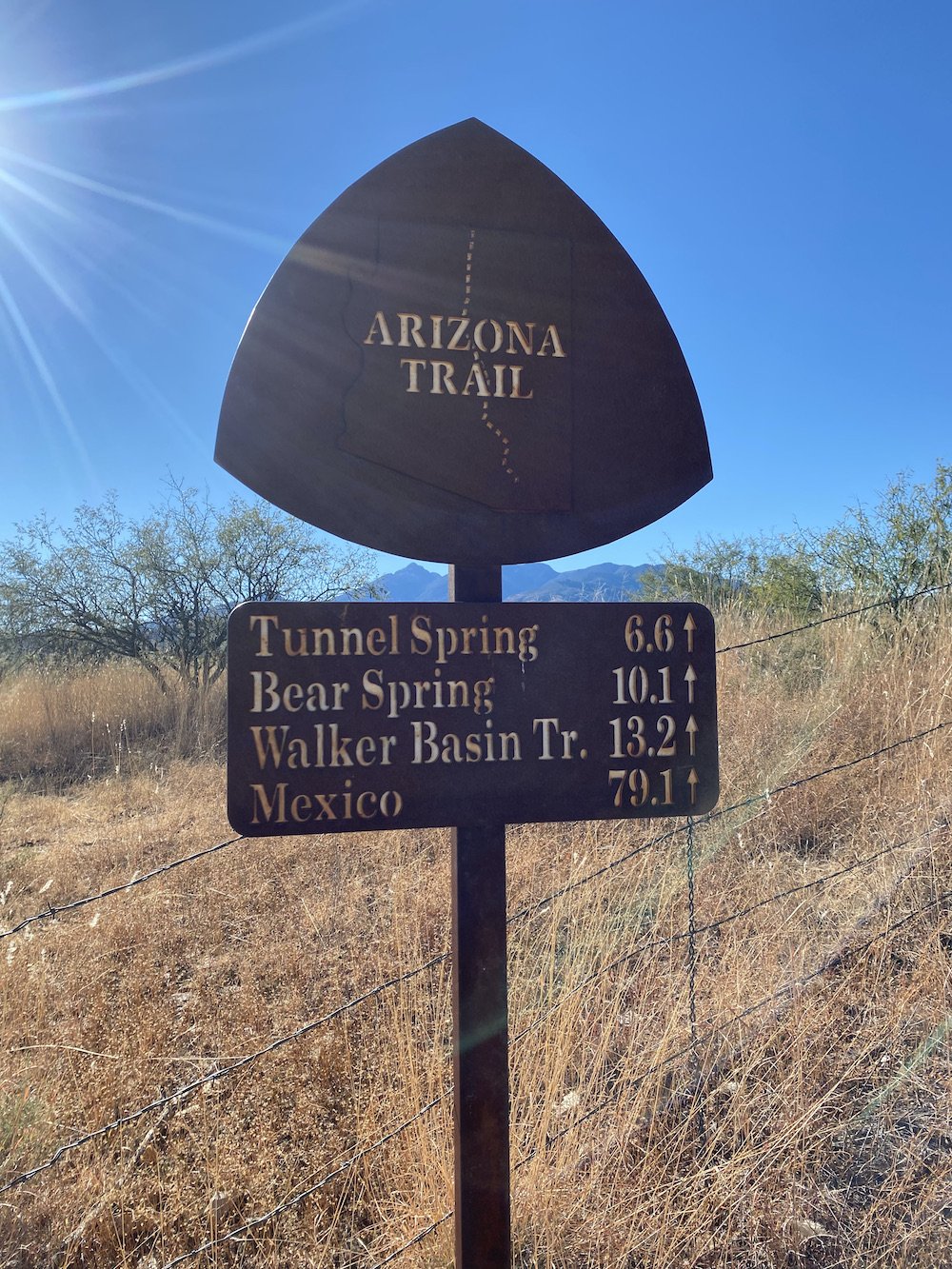

I had fewer than 80 miles left before I reached the border. My heart was buoyant, my steps, light.

The morning began with a climb over a high saddle in Mt. Wrightson Wilderness—a beautiful, but brief, stretch of woods—before I began the long walk into the town of Patagonia.

After clearing the saddle, the single-track ended, and my next 15 miles wound about on forest service roads.

I felt like I was moving slowly, and I didn’t see any water until I reached a small trickle running across the road. The area was heavily impacted by cows, and I was nervous the water would taste as bad as it had after Roosevelt Lake.

I didn’t have much of a choice, though, with several more exposed and hot miles between me and town.

I stepped off the road into a mucky but gently flowing portion of the stream.

I crouched down and filled my BeFree, filtering the water into my bottles, but afterwards I stood up too quickly, my arms flailed, hands still clinging to my bottles, and the rock I was standing on tipped precariously.

I came crashing down.

Crack!

Water gushed out of one of my Smart water bottles.

I scrambled to get the leak pointing upwards and save every precious ounce of water I could; my hip throbbed, my right foot was soaking wet, and I smelled like cow poop.

I cursed the creek and the tippy rock and the mud.

And then felt pretty dumb for doing so, and promptly apologized to nature for my outburst.

The water source was called Anaconda Spring, a name I won’t soon forget as it really “got” me.

I continued trudging the road; my wet foot dried quickly. I passed some horses in a small enclosure. They seemed happy enough and I chatted with them as I strolled by.

The Huachuca Mountains beckoned to me; their looming, indigo presence perched delicately on the horizon.

Save for the sparse, bleached-tan and golden hills rolling towards me, the mountains appeared like castles; they stood in stark contrast with the surrounding landscape, as if they were dropped from the sky.

I stopped in the middle of the road and felt just how far from home I was.

To see “the end” before me, was both sad and joyous.

I walked into Patagonia, full of want but without any real need.

Most of the restaurants were closed which made my choice not to stop for a hot meal rather easy. I purchased a sandwich, and an electrolyte beverage from the general store to replace my busted bottle.

I was at a loss for where to get water, then I saw a locked hose outside the post office and went inside to ask for the key.

I thought this was a great idea, but quickly realized my mistake when I took that first sip of water and the taste of hot, stale rubber hit my tongue.

I sighed with disappointment and kept moving.

On my walk out of town I called my parents and updated them on my journey.

The road back to the woods was a long one. I passed by an RV park and some private property. I really needed to pee, but there simply wasn’t a place to do so privately.

When I reached the trailhead, I noticed some gallon water bottles sitting next to the trail signs.

Blessedly they were full. I dumped the putrid hose water I’d been carrying, and took only what needed of the fresh water.

I still had a ways to go before reaching camp for the night. I had wanted to put in a longer day, and long it was…

Darkness fell and the trail grew thorny and nebulous. My legs were getting destroyed by sharp vegetation, and the area I was walking through felt eery; I had a sense that I was being followed or watched. Strange sounds floated towards me through the night—probably just cows—I reassured myself.

I powered through grass that taller than me, getting lost for a brief time in a wash. Frustration overcame me, I desperately wanted to find a place to stop for the night.

Eventually I spotted a tiny patch of bare ground next the trail, the fact that it was clear of thorns was a major bonus.

I pitched my tent quickly, stuffed my face with food, and passed out to the sound of a rain tapping lightly on my tent.

Day 34 (12/14/21): 28.5 miles & 5,700ft+

My second to last day on trail shaped up to be a beast of a day; all the water sources in the first 15 miles tasted like (pardon my language—this is a direct except from my journal) “straight-up cow asshole and ammonia”.

The after-burp was highly offensive and left an oily residue on my tongue.

To top it all off, I came upon an eviscerated baby cow—very fresh—in the middle of the trail, not 2 miles from where I camped the night before. Quite frightening, given that a mountain lion was most likely responsible for the kill [the next image is graphic, feel free to scroll past it but I felt it was important to include].

I was rounding a curve in the hill when I caught sight of a pair of giant, chocolate wings; they unfurled, spreading wide, and before I could decipher what I was seeing, a velvet, feathered dragon reared up to stare at me with a pair of piercing eyes.

It was huge. As tall as me. Its wingspan could have wrapped twice around my body.

The noise of its wing beats taking off from the small, sad carcas, was muted—either because my ears had stopped working or because the creature simply wasn’t real, just a figment of my tired imagination.

I was certain it was real, though—a golden eagle.

From what I understand, the golden eagle, in many cultures, symbolizes an ending; but in every ending, there is a new beginning. The golden eagle appears when it is time for a person to let go of the past and walk forward to meet their destiny.

I was struck dumb as I hiked on. I stepped around the gutted calf—a horrifying or beautiful sight, depending on whose perspective I viewed it from—and considered the unforgiving nature of the desert.

The terrain proved to be more and more exhausting as the day wore on; the trail went sharply up and down, over rocks and through thorns. I found myself saying, outloud, “This is so hard".” Over and over again.

Grouse exploded repeatedly from the brush, leaving me gasping in fear, and gripping my chest.

Those darn birds wait until the last minute to burst up in a flurry of feathers and flapping. They are a heart-attack waiting to happen.

Tiredness seeped into my bones around noon, all I wanted to do was stop walking and sleep.

But I continued winding my way closer and closer to the Huachucas, drawing nearer to their bulk with every leaden step.

I crested a final, golden hill and dropped into a wash; juniper trees surrounded me and as the trail trended upwards, they were soon interspersed with ponderosa.

I passed a sign for Miller Peak Wilderness as the sky grew dusky. This was it, the beginning of the end. Just one more mountain to climb.

I stopped at a fresh looking stream before camp, and filled up my water bottles for the night.

I was aiming for a large flat site some hikers raved about on the app and when I arrived to it, I was thrilled to find a plush, pine-needle-covered forest floor to sleep on.

The wind roared through the tops of the trees as I drifted unceremoniously to sleep; it sounded like a train racing through the sky, like the whole mountain was going to crash down around me.

I was too tired to worry.

It was fitting weather for a final night on trail.

Day 35 (12/15/21): 16 miles & 4,230ft+

Writing about my final day on trail was hard when I put pen to journal over two months ago, now, in the Tucson Airport. It isn’t any easier today.

I barely have the words to distill the experience, to make the intangible swirl of thoughts and emotions, into something concrete.

The fluid swell of feelings, the dazzling refraction of my recollections—like light bouncing off waves—must first be captured to be recorded. If left as memories, the story evaporates in a whisper, and is lost forever.

It is better than nothing, to write; it’s better than letting it all disappear.

I woke up at my usual time of 6:13AM. Gusts had shaken the trees around me all night, occasionally side-walling my tent, but my stakes had held firm in the damp soil.

The sky was grey and broody as I packed up and began marching uphill.

I was climbing into a cloud, which is a rather magical experience; I love reaching the “line” between the dry world and one soaked in mist.

The switchbacks which carried me up to the ridge were lovely and well-graded. I achieved a quick pace of 3.5 miles per hour and held steady.

The ridge was partially treed, and as I popped over into exposure, I was immediately battered by an exhilarating wind. Clouds swirled around me, blue sky breaking through above, the sun melting golden somewhere behind the blustery, mist-sprayed miasma.

I laughed out loud at the charged atmosphere. I danced across the exposed patches of ridge, feeling immense gratitude for the beautiful send off.

The trail then took me down to a relatively dry saddle, before it carried me up a final climb.

Bathtub Spring sat, in all its clawed-foot glory, about one mile before the junction for Miller Peak side-trail.

I stopped there and filled up on ice cold water from the constantly flowing spigot, which ran into the tub. It felt like a scene from Alice in Wonderland.

After my final water source of the trail, I charged ahead to the side trail. I wanted to go to the peak even though it was an extra mile round trip and a couple hundred feet of elevation gain.

To me, the peak marked the true end of the trail and I knew I’d regret it if I didn’t go for it.

I could see the summit before me, its frosted top peaking in and out of the clouds.

I was within its gravitational pull now, my feet moving quicker without my telling them to do so. My heart beat quickly, my lungs burned, I was practically running.

It felt monumental—my hike—the whole of it.

I was broken, wrecked, depressed, after tearing my ACL in January of 2021; I was relegated to crutches for two weeks proceeding surgery in March and then began an intensive physical therapy program which has lasted nearly 12 months.

I had no hopes of thru-hiking a long trail just 8 months after surgery. I had no idea what my life would look like after my accident.

Turns out life looks pretty beautiful; I’m happier now, after getting hurt and recovering.

I had a lot of inner work to do. And since I couldn’t ski or run or even hike, for all those months, I ventured inwards instead.

As I turned onto the side trail leading to the summit, I felt like I was turning a page in my story.

Every pine needle, every leaf, stem and branch, was encapsulated in ice, frozen in time, I prayed my memory of it would be too.

I hiked quickly, drawn ever upwards by the magnetic pull of the blue sky. I was above the clouds now, I just needed to see…

What was up there? What was below me—behind me?

And then I arrived.

I stood on a castle tower skirted by clouds; all around me rose dark indigo giants from the golden prairie, each dressed in a curtain of mist.

The wind pounded my rain jacket as I laughed, my heart sang, I felt free.

And that’s my “why”—freedom—to kindle my spirit, to unearth my truth, to see the world and myself, with piercing accuracy.

But as I stood there, gasping and crying and shouting into the wind, my gaze landed on something that didn’t belong, at first it looked like the longest straightest road I’d ever seen.

But I knew.

The wall raced with uninterrupted and deadly precision across the desert.

It appeared arbitrary from my vantage point, like a line an older sibling might trace into the carpet before the younger, “This is my half of the room, and that’s yours.”

It cut across the land in a blatant statement of ownership and otherness—of fear.

I shuddered to think of all the people who had died in the desert—their forgotten bones resting far below me—all the people who traveled away from their homes and loved ones, only to perish, thirsty, hungry, hoping.

When a pilgrimage into the Sonoran desert with naught but the clothes on your back and the water in your flesh becomes the better option, we have to ask ourselves, as Americans, what are we so afraid of, that we abandon these people instead of aid them?

But fear is contagious, it is like a disease. I tried to steal myself against it—I thought I was prepared—I wasn’t ready.

Because everytime someone asked me if I was carrying a weapon (I don’t), or warned me to always camp with other people (an impossibility), or referred to migrants as “illegals”(humans can’t be illegal), or told me that I could be killed if I ran into the “wrong people” as I got closer to the border(this could happen anywhere)—I felt the fear creep in.

It trickled down my spine, making me wary of the dark and causing me to peer suspiciously over my shoulder as I walked.

Then, one day while I was hiking, I found a red and white checkered blanket half buried in the sand and something in me broke.

Standing in the middle of nowhere with that filthy blanket at my feet, I remembered my humanity.

The people traveling from Mexico and South America, who attempt to migrate north across our border, are not making a choice, if they felt they had a choice, they very likely would not travel into this desolate place with something as impractical as a blanket.

I walk with my privilege every day of my life and I have been granted many advantages—this does not make me a bad person, it is just a fact.

I hike long trails because journeys like these bring me joy. My reason for walking is so different from these people who are attempting to cross a barren land to save their lives.

My heart aches for all those people who risk death with such a journey. I cannot fathom what it would like to die in the desert.

While none of us is immune to the fear, every one of us is capable of choosing compassion, of embracing vulnerability and empathy, of trying to understand why people migrate across the desert.

After spending time in communion with the natural world, I climbed down from the summit, I met a friend and fellow hiker, Bill, and we walked down to the wall together.

I hated to look at it and all it represented.

As I pulled my body through the barbed wire fence abutting the incomplete wrought iron barrier, I knew I was breaking the rules with my trespass.

Standing with the monument on the Mexico side of the border, I felt none of the feelings of completion and overwhelm that I’d felt on Miller Peak.

I was glad I’d come, I smiled for a picture, but my heart didn’t feel lighter for having “finished” in such a low place, metaphorically and literally.

My hike was over, but my journey was not.

Today, I don’t know where I am going any more than I did before walking 800 miles across the state of Arizona.

If anything, the more I walk, the more questions I have.