How to START Planning a Thru-hike

Because getting started is often the hardest part of any new adventure…

Hey, my trail name is Kaleidoscope and I have successfully completed thru-hikes of the Appalachian Trail, Vermont’s Long Trail, the Colorado Trail, and the Arizona Trail, in addition to completing a number of large section hikes ranging in length from 193 miles to 1,000 miles—that’s not to mention the number of adventures I’ve planned and have yet to tackle.

I love planning treks almost as much as I love taking them.

I spend an unreasonable amount of time bent over maps, scrolling through trail blogs, jumping between Gaia, AllTrails, FarOut Guides & Google Maps, studying resupply options Ad Nauseum.

I burn hours mile crunching, fleshing out every possible option to get “there” and back home; I dive down all the gear rabbit holes, chasing the newest-lightest-best etc. etc. until I find myself contemplating a pair of $40 ultralight camp “shoes” made out of cardboard—no, seriously.

Only once I’ve done my research, do I start making detailed route plans, the act of which strokes my subconscious until it is purring like a fat cat on a sunny cushion.

I remember my mom making a comment when I was still living at home and planning my “next big walk”, about the state of the dining room table and the sheer quantity of spreadsheets littering it being “concerning”.

And sure, on the table there was a lot of paper, but in my head I was already on the trail, living the adventure.

I was consumed with figuring how much food I would carry, when I would runout, where to stop when I did, if there would be a grocery store or if I needed to mail a box, how far the town was away from the trail—could I walk there or would I need to hitch?

BB, my grandmother and by far one of my biggest supporters when I thru-hiked the AT in 2017, would send me boxes of treats from Trader Joe's to various points along the trail. It was rad. I was considering how many pairs of shoes I would need; if I walked more than 500 miles, I would probably need to buy (or mail myself) a new pair of shoes on the trail.

I was thinking about how to keep my electronics charged; what size battery bank would I need? How often would I be in a town to recharge it? Was I going to use my GoPro to film the hike or just my phone for pictures? Would I need to re-charge my GPS watch? My InReach device?

It pays to ponder the small stuff, even if when splayed out on the dining room table meticulous is mistaken for obsessive.

In lieu of the messy dining room table, here is a photo of an equivalent scenario: the organized chaos that is the drying out of one's gear after a storm, otherwise known as a "garage sale". In addition to planning out the tangible components of my hike, I try to imagine the time I will be absent in a real way—”I will be gone on the 4th of July, I will miss the family cookout,” “I will be gone for Christmas and New Years and will miss spending time with my partner and his family,” not just, “I will be gone for 6 weeks.”

Six weeks does’t matter to me, I’ll give six weeks to the mountains in a heartbeat, but holidays, birthdays, weddings, funerals & family things do tend to matter. And if I am going to miss them, I want to do so with intention.

There comes a point, though, when the planning & imagining concludes and I just have to go walk, of course, that is when pretty much everything I thought I had nailed down goes flying out the window.

Pre-800 mile walk across the state of Arizona (aren't my shoes so pretty and new?!)Even if everything falls apart the minute you hit the trail, time spent planning is not time wasted!

And so, to aid you in making your own thru-hike plans, I took my rather chaotic planning process and distilled it into three simple phases:

Phase 1: Information Gathering

Information gathering is fun, plain and simple. It involves reading blogs, watching vlogs, downloading the appropriate trail guide or GPX file for your route, joining a facebook group which focuses on the trail you hope to hike, following other hikers on social media and reading their posts about the trail, purchasing a hard copy of a guidebook from the trail association.

I love this first phase of planning because it gives me a chance to dream and decide if a specific trail is right for me.

Details I consider while information gathering include: the direction I want to hike the trail and what season makes the most sense for my journey (sometimes one dictates the other), how quickly I’d like to move, how many—if any—days off (zero days) I want to take, how light I want to keep my pack, if I will travel alone or with friend(s), how much the adventure will cost, how much time the trip will take, the history of the trail and the land it travels through, and whether or not I will need a permit to hike the whole trail or individual permits to traverse certain areas it passes through.

In this early stage of planning I want to ascertain what, if any, major obstacles might arise before or during my hike, for example, trail re-routes due to erosion, fire, or flooding, annual trail closures due to wildlife mating seasons, pandemics, etc.

Basically, this phase asks the question: Is the hike possible? And guides you through finding the answer.

Phase 2: Make an Outline

Once I establish the trail I’m interested in is the right trail for me at this point in my life (timing is important!), I begin to outline what my hike will actually look like.

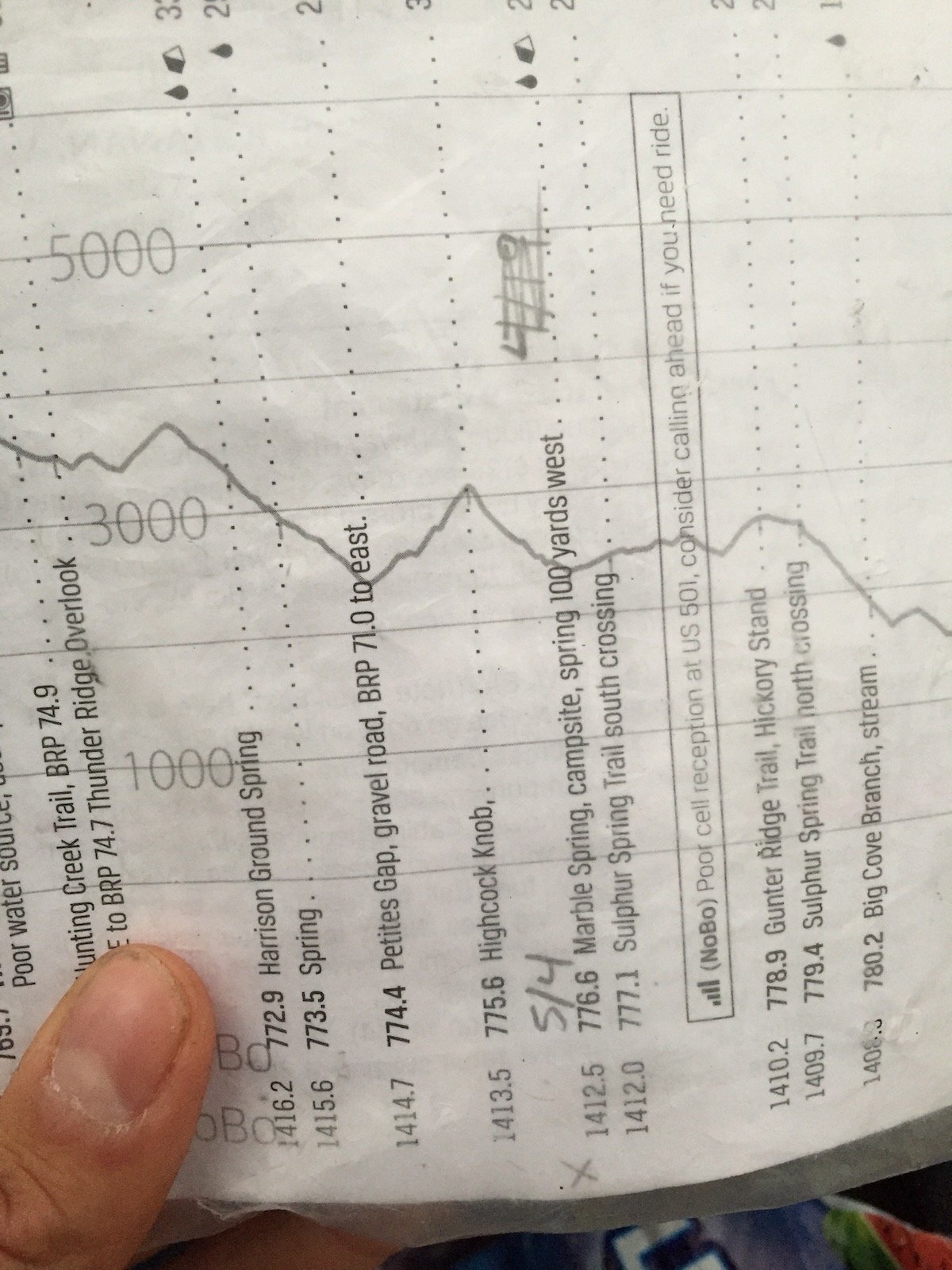

Your outline doesn’t have to make sense to anyone but you. I use a lot of abbreviations & different colored highlighters; I denote mile-markers, relevant town and road names, I keep track of total miles, miles between campsites, resupplies, etc., and I mark any campsites/town stays which require advance reservations (see the examples of my old CT & GDT plans below).

At this point, it is easy to become deeply attached to the plan. But while you are sitting at your computer in your PJ’s ordaining that Future You will walk 25 miles on day 5 in order to get to a resupply that much faster, it’s important to remember things may go sideways.

You might get terrible blisters that slow you down, you might get your period and feel positively horrible or, on a more positive note, you might find you have extra food in your pack and decide to spend a bonus night camping near a gorgeous lake.

Future You may want to change her plan and she reserves the right to do so.

Outlines are meant to be broken!

There are so many variables we cannot predict; the ultimate purpose of making a detailed plan is to be as informed as possible and have something to fall back on when things go awry.

Phase 3: Fine Tune

In order to feel confident in your plan, the research must continue. Forever. Fine tuning is an ongoing process beginning in advance of your first steps on trail, and continuing well beyond the completion of your hike.

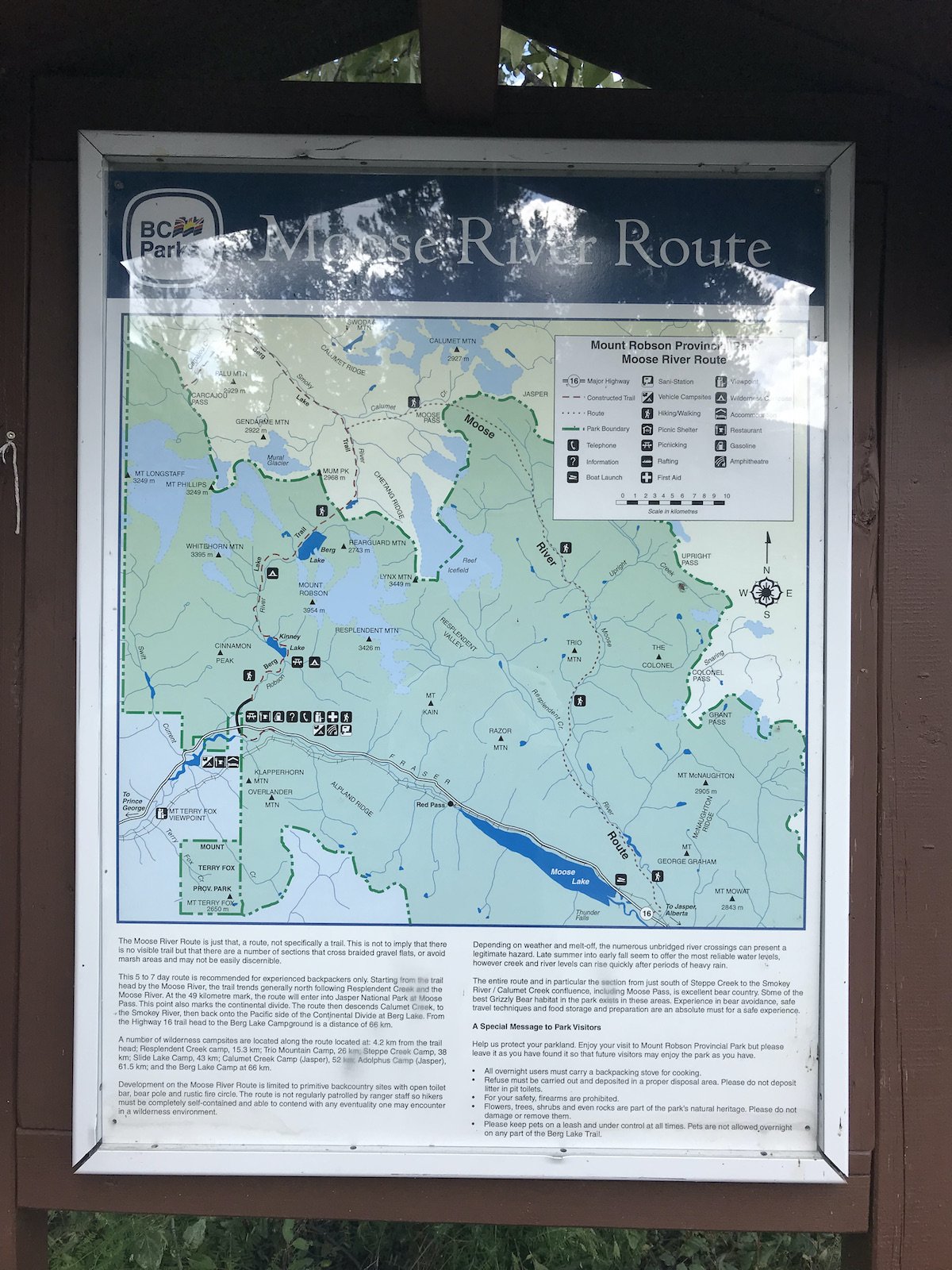

A personal example: In 2019 I made detailed plans to thru-hike the Great Divide Trail in BC/AB, I did all the research I possibly could in advance, but I never could have prepared for what I found when I reached the edge of Jasper National Park, on the other side of Mt. Robson Provincial Park.

Suddenly I was standing in the wildest, most remote, rugged environment I’d ever experienced and I was afraid to cross the Smoky River.

Exhibit A: The Smoky RiverOnce I accepted that 2019 wasn’t the year for me to thru-hike the GDT end to end, I turned my trip into a scouting mission and began information gathering anew.

I hiked sections of the trail, I practiced my route finding skills, I got used to the hugeness of the terrain and sheer size and force of the rivers. I made friends, went sky-diving, and generally had a great adventure.

An alternate route I attempted in order to avoid the Smoky River; it made for a great 28 mile out and back, seeing as I was also afraid to cross the Moose River when I reached it. Research can be fun and it will really test your commitment to your goal.

Go on some scouting missions, place yourself physically on the trail, call ahead to any businesses you intend to send a resupply box to, confirm the hours of the post offices you intend to utilize, make reservations at hostels, hotels, & campgrounds in advance (but not too far in advance), basically, do your future self a favor and take some of the work off of her plate.

Even if your hike is a screaming success and you make it to the terminus feeling like you wouldn’t change a thing, you just might get the itch to go back out there someday.

Don’t stop learning about how you can be a better thru-hiker; the opportunity to reflect post-hike is not one to be squandered. We can always be better stewards, and more respectful & informed travelers on the land.

Leave Room for Spontaneity

Even with really detailed plans made, there will still plenty of room to wing it on your thru-hike.

Blisters, pack chafe, random sore muscles, hiker-hunger, hitching rides, miscounting miles, forgetting what direction you are supposed to walk when leaving camp, suddenly hating the food you mailed yourself, making friends, walking extra miles, walking fewer miles, camping on a special mountain with a killer view, night hiking, soaking in the most beautiful sunrises, eating the best burger of your life, falling in love with the trail, with life, with people—if nothing else, thru-hiking will surprise you.

There is nothing singularly special about anyone who has ever thru-hiked a long trail, one day we just started, and so can you.

“The best journeys are the ones that answer questions that at the outset you never even thought to ask” —Rick Ridgeway, an adventurer

Butterfly House, the best hostel on the Colorado Trail