The Wind River High Route

Andrew Skurka’s 100 mile route from Bruce’s Bridge TH to Trail Lakes Trailhead

Lynn on the descent from Blaurock Pass

Day 1: August 30th, 2025 // 15.8mi, 4308ft+

Bruce’s Bridge TH to △ before Wind River Peak

The sky was hazy as we drove past Lander with Mike, our shuttle driver, on our way to Bruce’s Bridge Trailhead. We left my truck at the northernmost end of our route, that way if we finished a day early or a day late, we wouldn’t have to coordinate a pickup.

At the trailhead we waved goodbye to Mike and I felt a measure of relief that our only option now was to walk.

“Shall we?” I gestured at the bridge.

“Let’s go,” Lynn said.

Bruce’s Bridge TH

Our first day was all on trail and all uphill, but the climb was gradual. Six miles in, the sky exploded with sudden ferocity; fingers of lightening shot through the clouds followed closely by intense claps of thunder. We didn’t know what the terrain was like ahead, so we waited in a cluster of tall trees for the storm to pass. Rain beaded on our Gor-Tex raincoats as we stared nervously at the sky. I wondered if every afternoon would be like this; I steeled myself just incase.

We opted to camp above Deep Creek Lake 9 miles later, where the trail faded into non-existence. Tomorrow morning we would begin the true climb to the summit of Wind River Peak, where the heart of our adventure would begin.

Outlet of Lower Deep Creek Lake

Day 2: August 31st, 2025 // 13mi, 4570ft+

Wind River Peak to △ at Lonesome Lake

The first 3.6mi of our day took greater than 6hr to achieve. In my journal I wrote of the West Gulley as “a heinous thread-the-needle of doom”. But allow me to rewind to our dawn hike to the summit of Wind River Peak:

Looking ahead to the tundra ramp to Wind River Peak

Dreamy orange light melted over the tundra as Lynn and I began our climb up the giant ramp on the north easterly flank of Wind River Peak. Soon, spongy tundra grass transformed into a sea of undulating rock. We used our hands to hoist ourselves up and over boulders the size of coffee tables and refrigerators until we reached the chunky granite summit.

Ivey on the climb to Wind River Peak

From 13,120ft we could see far ahead along our route, possibly all the way to our final peak, Downs Mountain, if it weren’t for the haze.

View from the summit of Wind River Peak; the visible lake is Black Joe Lake and the West Gulley lurks bellow the frame to our left

After a quick break we began the initially rolling descent off the summit. We didn't have a gpx file for the route, just a handful of waypoints and annotated paper maps provided by Andrew Skurka, the route creator, so I wasn’t sure of the exact angle we needed to achieve to enter the gulley, it would be a game of trial and error.

At first our angle of descent was too steep, heading us to the precipice of a thousand foot or greater cliff face. We changed course and angled back as if we were going to pass beneath the summit, staying high. Our trajectory became clearer the further we descended, keeping our angle of decent gradual.

Across the bowl the hanging glacier cracked and exploded as the sun warmed the ice. Rocks fell beneath it and careened down the steep slope, startling us both.

At last we were above the bedrock slabs we needed to down-climb for ~100ft; this was the crux of the West Gully. It looked bad. Lynn suggested we traverse a little more before descending; I’m glad she did. Directly beneath the bedrock we could see was a shear cliff face we weren’t aware of until we completed the down climb and looked back from whence we came.

Lynn descending the upper portion of the West Gulley

Lynn down climbing in the 100ft, 3rd class portion of the gulley

I went first and spotted Lynn from bellow, pointing out hand and footholds. By the time we reached the steep scree below the bedrock down-climb we were both shaken, but my nerves may have had more to do with adrenaline and excitement than true fear.

Lake of glacial melt-water in the upper basin bellow the West Gully

We stopped at the frigid turquoise lake in the upper basin to dry our dew saturated gear in the sunshine. I spread out the tents and our sleeping bags on a large rock. Lynn seemed quiet; I asked her how she felt.

“Do you think we will have to do anything like that again?” She asked.

“No, I really don’t. Everyone says the West Gully is the worst part of the whole route.” I smiled encouragingly at her.

“I thought I was going to die and I don’t think this is worth dying for.”

I thought for a moment before responding. “I know that was really hard—I was scared too—but we did it and I think that is pretty cool.”

The hike down valley to Black Joe Lake

The valley opened and greened up all around us as we followed the stream flowing out of the glacial lake. We hiked mostly in silence and my mind was free to wander over the majesty of this place. The water shone utterly clear, late season wildflowers wagged in a gentle breeze, boulders the size of shipping containers dotted the length of the valley.

Stepping around one particularly large boulder I paused, looked up from my feet, and locked eyes with a giant bull moose standing not 15 feet in front of me. He raised his large head and considered me over his giant nose, looking as surprised as I felt.

“Oh shit!” I waved at Lynn to cross to the other side of the stream.

She was closer to me than I thought and had seen the moose already. We both crossed the stream, looking over our shoulders several times as we did so. The moose was moving on, climbing away from us and the stream.

Our bull moose making his retreat

The hike around Black Joe Lake was a straightforward one on intermittent trail; at its end we climbed up and over a sheer bluff on a good trail, negotiating a steep down climb at the end to bring us back to the lakeshore. From there we followed good trail to Big Sandy Lake, a popular destination for hikers.

Wildflowers near Black Joe Lake

Lynn at the base of the bluff down climb

We passed Big Sandy Lake and began to climb towards Jackass Pass and I was immediately overwhelmed by the number of people hiking towards us. Every two minutes or so we stepped off the trail for groups of two or four or more as they made their way down to Big Sandy. I realized this portion of our trek must overlap with the popular Cirque of Towers Loop and groaned internally.

Lynn seemed relieved to see people; I knew that feeling from my more solitary thru-hikes but couldn’t seem to connect with any enthusiasm. The crowds thinned as we reached Arrowhead Lake and circumnavigated its boulder studded west bank.

The climb from Arrowhead Lake to the pass was short, having the majority of our climb behind us by that point. Lynn reached the sign first and put her hand against it. I realized this was an important part of the hike for her, she’d really been looking forward to reaching Jackass Pass and the Cirque of the Towers.

I had to admit the scene was iconic and my mood lifted slightly after being dragged quite low by the onslaught of people and the repetitive conversations we’d had with them in passing.

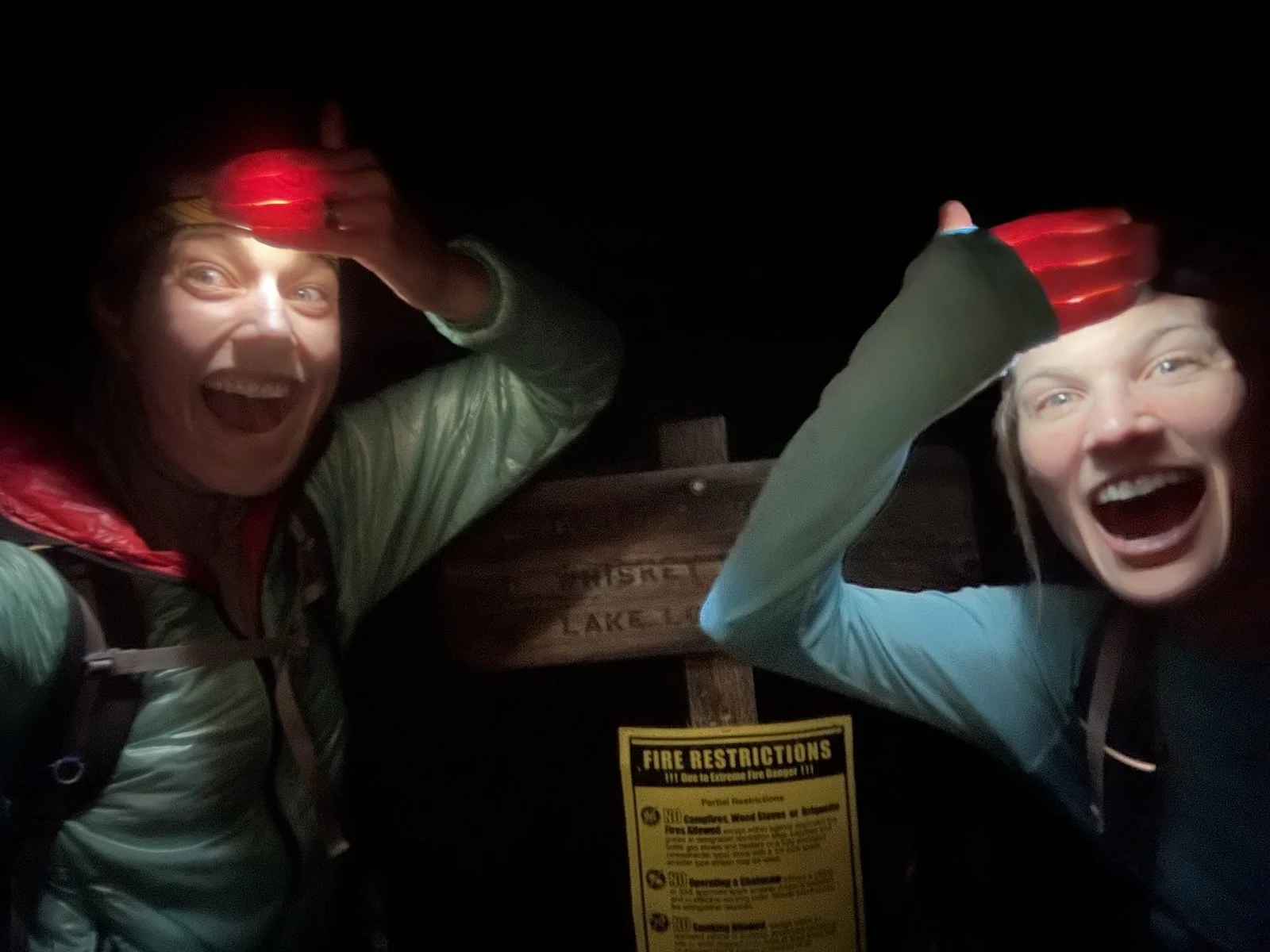

Jackass Pass celebration

We descended from the pass to make camp a quarter mile above Lonesome Lake, which we opted not to filter water from as it is quite polluted from all the hikers and climbers that camp in this basin (read about lake pollution here).

I boiled water and rehydrated our meals while Lynn finished setting up her tent. Over dinner we talked about our expectations for the rest of the trip.

“I’m just happy to be out here,” Lynn said. “I don’t feel the need to do the more challenging route, necessarily. After camping tonight this will be one of the longer backpacking trips I’ve been on.”

“Sticking to the route is important to me,” I said. “The West Gully sucked—it makes everyone who hikes this route want to bail—but it’s behind us now and we should feel proud of that.”

“New York Pass doesn’t look fun either, though.” Lynn took a bite of her curry.

I sighed. It was true, NY Pass was our way out of this basin and it looked like a giant wall of scree. I knew it couldn’t be worse than what we’d done this morning but since I’d never done the route I found myself struggling to reassure Lynn. She said she’d rather do Texas Pass which her husband had done in years past; it had a trail up and over. I felt resistant to this deviation.

We went to bed without speaking much more and I did not sleep terribly well, worried as I was over the success or failure of this adventure.

Ivey consulting the map atop Jackass Pass, the Cirque of the Towers in the background

Day 3: September 1st, 2025 // 16.8mi, 4298ft+

Texas Pass to △ at Lee Lake

In the morning while packing up I offered that I’d be willing to do TX Pass instead of NY, in this instance, if Lynn would be willing to continue on route after. She expressed concerns about the unknowns that lay ahead, and in response I told her I truly believed the worst was behind us.

We shouldered our packs and began our hike around the lake to the base of Texas Pass.

Still waters of Lonesome Lake

We ascended steeply and the hiking was great, on good trail with even better views. Fuchsia wildflowers grew in profusion alongside gurgling rivulets of water and the sky was so clear and so blue it almost hurt to look at.

View of Pingora Peak along our climb up TX Pass.

At the top of the pass we paused to take pictures at the sign, conversation flowing easily between us.

I realized I needed to let go of the rigidity I employ on my solo ventures in order for this adventure to work. I resolved to be more openminded going forward.

Our shadows near the top of TX Pass

The hike around Texas and Barren Lakes was easy and quick. Even when we rejoined Skurka’s route at Billy’s Lake the hike remained fast. We passed Shadow and Skull Lakes before it was time for us to leave good trail in favor of cross country travel to join the East River Valley.

Lynn on the descent to TX Lake

Leaving the trail felt jarring. We veered left into an open forest of fir trees, making our way generally West and down to the confluence of the East River and the outflow from Mary’s Lake somewhere to the North East.

Exiting the forest onto bare slabs of granite replete with cascading water, we took our bearings and began threading our way up valley alongside the East River.

Looking up the East River Valley

The valley widened as we climbed. I was careful to make sure we stayed alongside the East and didn’t turn up any one of the streams that flowed into it from our right. When we reached the upper end of the valley we pulled out the map and I told Lynn where I thought we were headed from here, to reach Raid Peak Pass.

Raid Peak towered above us on our left, a sheer wall of granite, and directly in front of us lay Mount Bonneville, an equally imposing figure.

I pointed at the grassy ramp before us Skurka mentions in his guide book and then beyond it to the wall of scree that wrapped out of sight behind Raid Peak.

“Our pass is somewhere behind Raid Peak,” I said. “We can take this ramp to gain the shelf and traverse across until we can see our climb up more clearly.”

”We aren’t climbing that peak?” Lynn gestured at Bonneville.

“God no!” I said.

“Oh thank goodness. I thought we had to summit.”

We both laughed and I was relieved that she was relieved.

Attaining Raid Peak Pass was straightforward navigationally, but involved climbing over a sea of unsettled, giant boulders. It was mentally demanding to say the least. Once at the top, we descended slightly to the west into a shallow bowl, then climbed barely more than 100ft to the north over a saddle.

Lynn climbing lower down on the route to Raid Peak Pass

Lynn near the top of Raid Peak Pass

From where we stood on the saddle, the slope before us appeared to end abruptly, dropping off into nothingness.

“The map shows us staying towards the middle,” I said and we started walking.

The terrain opened up as we progressed; with each step we could see a little more of what was coming. Lynn found a way down she preferred to the bedrock slab Skurka spoke of and after some discussion, we scrambled down the chimney she’d spotted. She employed a move we came to call “The Reverse Gumby with Added Friction” and I followed behind in a slightly more traditional fashion (but with far less grace) after passing her pack down.

Looking back up at the Raid Peak Pass descent (looks easy peasy from here, doesn't it? Pictures don’t do it justice.)

At the base of the descent we were chatty with adrenaline, laughing about Lynn’s feat of friction sliding down a particularly grippy rock.

The hardest part of the day was behind us and we decided to proceed around Bonneville Lake to Sentry Peak Pass.

Lynn hiking around Bonneville Lake toward Sentry Peak Pass (center of the photograph).

The pass was a straightforward climb on a series of grassy ledges and large boulders, never exceeding class 2+.

We had fun with the ascent, cracking jokes and reminiscing about the horrors of the West Gully.

Lynn on the climb of Sentry Peak Pass

We topped out as dusk began to creep across the valley. Lee Lake, our destination for the night, looked far away but our spirits were high as we navigated the descent, staying high to avoid dense willow as the guidebook recommended.

A view of Lee Lake, touched by the last rays of sunshine in the distance

Darkness fell just as we finished pitching tents and boiling water for dinner. I rehydrated our meals and we talked about where to tie our Ursaks for the night. I was paranoid about a bear taking our food and running away with it, so I hung the sacks within earshot. I would absolutely fight for our food or at least scream at the bear, a lot.

I crawled into my sleeping bag and slept well after a long day of walking and navigating.

View of my tent, looking back up valley from our camp near Lee Lake

Day 4: September 2nd, 2025 // 6.5mi, 1749ft+

Photo Pass to low △ before climb to Europe Peak

Bewmark Lake below Photo Pass

Our fourth day on trail was a kind and short one. We climbed away from our camp at Lee Lake, wrapping above the east end of Middle Fork Lake, as dawn broke soft and warm around us. I could see the steep lip of the bowl we needed to attain to reach the basin below Photo Pass, our next objective.

The steepness and thick willow relented as we cleared the lip and gave way to a view of the glassy stillness of Bewmark Lake.

Lynn approaching Photo Pass

After clearing the lake, the climb to the pass was straightforward, Lynn even found a trail through the scree making our progress quick. The wind was blustery at the top of the pass and, much as I wanted to sit and have a proper snack, we didn’t linger long.

Descent from Photo Pass, looking ahead to Europe Peak

We walked the length of the marshy valley past Pipe Organ and Halls Mountains to the west, before beginning the long climb toward Europe Peak and what would be one of the most prolonged exposed sections of our route.

As we wove our way through the trees we could see clouds building overhead. Both of us expressed some nervousness about clearing tree-line if a storm was coming, and so decided to stop for the day and tackle Europe Peak early the next morning.

Day 5: September 3rd, 2025 // 17.8mi, 5449ft+

Europe Peak to △ on Kettles in Alpine Lakes Basin

Dark start in the forest below Europe Peak

Sunrise on the climb to Europe Peak

We woke up to our alarms at 3:30AM and were moving by 4:30AM. It turned out that we still had quite a bit of hiking to do in the trees and the way was not straight forward. Walls of granite rose before us, materializing out of the blackness, creating a maze. At each road block we scanned the dark for a way through—Lynn’s brilliantly bright headlamp was invaluable for this—usually finding a grassy ramp up and around the cliff band only to run into another wall of rock. A steep ravine dropped off to our left and we were careful to avoid its edge even as we zigzagged back and forth on ever steeper ledges.

It was an exercise in tedium and it seemed like we weren’t making any progress but I promised Lynn we were. We were moving over a mile an hour which we probably wouldn’t best by much even in daylight.

View toward Milky Lakes from the saddle below Europe Peak

The sky turned the muted, dusty colors of dawn as we reached the saddle below Europe Peak. We heard the ethereal bugling of elk and the pounding of their hooves as they peeled out of the terrain below us and charged into the valley.

View of Europe peak and its abrupt face

Europe Peak contained our final class 3 crux and we were both eager to get it over with. I thought it might actually be fun, since we’d be climbing up rather than down and it turned out that was absolutely the case.

Lynn and I discussed our path of ascent from the base of the climb and were in agreement on our trajectory. We stayed left, but not so far left that we fell off a cliff, and navigated the series of grassy ledges until the tundra ran out and rock was all that remained.

Climbing Europe Peak at dawn

We smiled and laughed most of the way up Europe, even as we negotiated the crux.

Lynn climbing Europe’s 3rd class crux

Lynn climbing the subsequent knife edge

The stoke was high as we traversed the knife edge to the wide 200ft scree field before Europe Peak’s summit!

Ivey celebrating on the knife edge

Ivey standing on the summit of Europe Peak

A view of the descent from Europe Peak under a distinct haze of smoke

The descent from Europe Peak was rather mindless and once the adrenaline from the summit wore off I realized I was pretty tired and hungry. We needed to make miles, though, so I didn’t ask for a break. We stayed high until it was time to descend the correct drainage to Golden Lake.

Golden Lake and beyond it, Lake Louise and Upper Golden Lake

We joined the Hay Pass Trail at Golden Lake and followed it up valley towards a wall of scree that guarded the highest lake below Douglas Pass.

Two groups of hikers passed us going the opposite direction in low spirits. The first was a couple and the girl was downright pissed; I greeted them, asked how their trip was going and the girl replied with one word sentences and gave me a dirty look. The next group looked bedraggled and pained; the guy in front confessed their trip wasn’t going well.

I was worried the negativity would shake our confidence for getting over Douglass Pass—another steep wall of scree like NY Pass, but without the class 3 moves of West Gully, Raid, and Europe.

“What do you think?” I asked. We stood on a boulder across the uppermost lake from Douglas Pass, inspecting its vertical nature.

“I don’t want to do it but I also don’t want to deny you this experience.”

“I really don’t think it’s going to be scary, just a suffer-fest,” I said. “Can we try?”

“There’s an alternate around it, I’d prefer to take that, but if this is important I’ll do it,” Lynn said.

I kept my gaze trained on the wall of rock that loomed across the lake from us. I didn’t want to be responsible if the pass sucked, and I knew it would, but I also knew we could totally get over it.

“Okay.” I felt myself let go. “We can go around this time, but I really don’t want to detour again after this.”

View of Douglas Pass (furthest right) from across the lake

We opted for the Camp Lakes Alternate which actually was a part of the Dixon version of the WRHR, a more popular route that utilizes vastly more preexisting trail and is generally viewed as easier. Ironically the crux of the Dixon Route was on this alternate, and it was not easy at all.

Unnamed Lake beneath The Fortress (right-most mass)

We hiked around the far side of Camp Lake and I had a meltdown about how minimal the information was that we had for this alternate route. I was worried about navigation and Skurka’s vague remark about a third class down climb beneath a precariously perched boulder above the lake.

Despite my misgivings we pressed on and encountered another group of Dixon hikers who’d just come down from Alpine Lakes area.

“How was the crux move?” I asked.

“Oh it was nothing. You won’t have any problems.” They told us.

And when we got there I decided they must have blacked out the entire experience because it certainly wasn’t nothing and we did have problems.

Looking back at the class 3 down climb

Lynn navigating the boulders of the Alpine Lakes region

I was furious (or maybe just very scared) that we’d deviated from the route only to have to navigate a heinous down climb that seemed to lean out—in vertigo inspiring fashion—over the glacial blue of the lake. The entrance to the down climb was on a steep, grit-slick hillside. I imagined wiping out and sailing right over the edge due to the weight of my pack.

Lynn went first; I was grateful for her problem solving attitude because I had pretty much shut down that part of my brain for the moment.

I passed her pack down and then mine, then made the awkward move over and around the boulder that was wedged in the gap. I could see this being an easier maneuver in reverse (climbing up instead of down), the direction most all Dixon hikers travel, but I certainly struggled.

Despite only have about two miles to camp, the hike took us three hours. There was not a spec of flat ground, or any ground at all, until we reached the kettles and made camp on a few sparse patches of tundra.

The smoke had rolled in thick by now and white flecks of ash were falling from the sky onto our tents. Lynn was concerned about fires and air quality and while I acknowledged the conditions were less than ideal, there wasn't much we could do about it. No fire could reach us in our granite fortress and the Alpine Lakes region on the High Route was very remote; the only way out was through.

Smoke rolling in over the kettles

Day 6: September 4th, 2025 // 10.4mi, 4720ft+

Alpine Lakes Pass to △ before West Sentinel Pass

Looking back over the middle lake in Alpine Lakes Basin

We decided to start in the dark again, waking up at 4:30Am this time, to get ahead of storms. I didn't mind navigating in the dark and the way went smoothly for the most part.

At the upper most lake below Alpine Lakes Pass, we needed to climb up and around two significant bluffs on the western shore. The first was straightforward, the second involved gaining about 300ft to fully circumvent the last bluff.

Towards the top of the bluff, or what I thought was the top, I saw a ramp that ran up a gradual sort of gully and suggested we take it.

“Are you sure we are high enough?” Lynn asked.

I wasn’t, but I had a feeling and the feeling paid off. We were pleased to see that we didn't need to descend all the way to the lake again to reach the pass, we could drop slightly, then traverse and climb from there.

Lynn on Alpine Lakes Pass

The climb to the pass was steep and I broke out my micro-spikes so that I could climb a ramp of frozen snow and take a break from the boulder jumble. Once we hiked across the pass we had a stellar view of the Knife Point glacier across the basin which had been a favorite section of the group of Dixon Route hikers we’d chatted with. We wouldn’t cross the Knife Point Glacier on our hike, instead, on the following day, we’d cross Gannett and Grasshopper Glaciers.

View of the knife point glacier from Alpine Lakes Pass

Our descent off of the pass was nebulous and long, when we finally reached the river valley below (unnamed) we felt as though we’d entered a verdant wonderland, full of Krummholz Spruce and wildflowers and turquoise water. We hadn’t seen such lush vegetation since earlier in the morning on the day prior.

We traipsed down the river, stunned into a silent sort of awe. What a beautiful place and how lucky were we to be here?

The most beautiful places are often, in my experience, the hardest to reach.

Lynn walking in the unnamed river valley after Alpine Lakes Pass

Eventually we turned north up a steep valley and cleared a wide saddle with a slate colored lake in its rocky middle. We saw several sheep leap up the rocky slope to our right like it was nothing, before we began our slow descent to the North Fork Bull Creek valley beneath Blaurock Pass.

Ivey standing on the saddle before North Fork Bull Creek with a view of Blaurock Pass across the way (see widest pass, furthest to the right)

We’d caught sight of the imposing pass on the saddle and Lynn had expressed some nerves. I agreed that it looked absurdly steep, but that I thought we’d make quick work of it.

It was not quick, in fact, it was the opposite of quick. Never in my life have I seen so. many. rocks. We cleared one wave of moraine after another, sometimes losing sight of one another as we chose different paths through the wreckage. Lynn would shout, “Over here!” And I’d crane my neck until I caught a flash of her blue sun hoodie between gaps in the rock.

Eventually we reached a sort of rocky ramp with patches of tundra peeking through, and then it was a straightforward and steady slog to the pass.

Lynn negotiating the moraine field below Blaurock Pass

View of a hanging glacier on the other side of Blaurock Pass

The rocks became much smaller towards the top; at one point it felt like we were walking on sand. As soon as I cleared the gap I was pummeled by wind. It roared loudly in my ears and Lynn was gesturing to descend quickly. I nodded and followed her down until the wind relented and we could stop for a break.

Lynn on the final push to Blaurock Pass

We studied our options for descending once our trail through the scree deteriorated. It seemed we could jump into the gully to our right or stay slightly higher and negotiate a ledge system on bedrock slab. I pointed us towards the friendlier looking slabs and we zigzagged our way down to the tundra.

Lynn descending from Blaurock Pass

After descending Blaurock Pass we reached the opaque, glacial waters of Dinwoody Creek, which I imagine is a formidable ford earlier in the season. Even as low as it was for us in September, it was still quite wide, moving at a steady clip, and shin deep in places.

The mile and half up valley from Dinwoody was maybe our slowest yet. The moraine was covered in grit and gravel and wildly unsettled. We saw cairns everywhere and finally gave up trying to follow them. The campsites mentioned in the guidebook were only visible once we were standing directly in them.

The smoke relented during the day and the air had been quite clear until we rolled into our rock camp below West Sentinel Pass, where the smoke descended once more, thick and brown. Black pieces of ash rained down on my tent and the sky took on the qualities of an angry bruise.

Over a dinner of rehydrated Mac and cheese for me, and curry for Lynn, we discussed the next day. Originally we’d planned for two more days, finishing on the 8th day, but the smoke was getting to us.

Lynn asked, “Do you think it’s possible to finish tomorrow night?”

We only had 25 miles left and about 8 of them would be on trail at the end.

“I think so,” I said. “I’m sure the glacier travel will be a little slow, but I think we can get it done.”

Camping below West Sentinel Pass with a view of surrounding glaciers

Day 7: September 5th, 2025 // 25.8mi, 5584ft+

West Sentinel Pass to Trail Lakes Trailhead

We set our alarms for 4:30AM and we were hiking again by 5:30AM. The climb up West Sentinel Pass was as straightforward as any boulder scramble can be, and topping out at the toe of the Gannett Glacier at dawn, smoke aside, was magical.

Lynn tying her shoe in the dark before the hike up West Sentinel Pass

View of Gannett Glacier from the top of West Sentinel Pass

This glacier was special for Lynn, her dad had come here on a NOLS trip years ago and summitted Gannett peak, so we took our time hiking across its gravel studded ice, pausing to get water from a runnel.

The Gannett Glacier

Walking on and around the edges of a glacier is a bit like being in a demolition zone; it is a place of rapid and extreme change. Ice melts and shifts; walls of rock debris collapse with little warning; holes at the meeting place of ice and earth gape to swallow pounding cascades of meltwater.

Our departure from Gannett Glacier lead us to a steep, sandy pass that didn’t look like much of a pass at all on the map because the glacier used to be near level with its lip.

Lynn getting water from a runnel on the ice

Looking back at an unnamed pass beyond Gannet Glacier

Beyond the saddle we wound our way across a shallow bowl full of unstable, sand coated rock and then began to climb once more. We negotiated the boulder studded shore of a small lake, squeezing along its west edge, a sheer wall of ice immediately to our left. I couldn’t help but stare nervously at the boulders perched precariously on the lip of ice 30 feet above us. I wished I had a helmet, but then again, if one of those rocks fell on me, a helmet absolutely would not help.

We were both tired from the early start and previous six days of technical travel, as the terrain grew more nebulous and decision making became harder, I could feel myself getting grumpy.

As we cleared the pass though, and Grasshopper Glacier came into view, we marched excitedly toward it.

Lynn crossing the moonscape before Grasshopper Glacier

At first glance, Grasshopper Glacier looked straightforward, but as we hiked up the slope and reached its convexity there were a shocking number of cracks, some of them person sized. The only notable crevasse we crossed on the Gannet glacier had been welded shut by pressure.

A deep runnel to our left which ran up slope seemed to mark a point of widening for all of the crevasses, so we veered right, doing our best to zigzag through the maze of icy rifts. When the cracks to the right began to gape wider, we trended left, and so on until we topped out on the ice and firm ground came into sight.

Entrance of the Grasshopper Glacier

Crevasses at the height of the Grasshopper Glacier

I felt a bit frayed, having fallen in a crevasse in Patagonia, but Lynn reassured me that we’d done it, we were through. I breathed out a sigh of relief when my shoes touched gravel.

We hiked a little farther before taking a break on a sunny tower of bedrock, looking back the way we’d come.

“Is that a person?” Lynn said.

“Oh my gosh, yes!”

A tiny figure morphed into a full-size hiker as it drew nearer.

“Hello.” The bedraggled figure waved to us.

His small pack, seemingly held together by duct tape, looked as though it was about to fall from his shoulders but he was all smiles. We greeted him cheerily and asked him about his hike.

“This is my second time on the High Route so it’s going pretty smooth,” he said. “I camped on the descent down Blaurock last night.”

He was moving fast. After a quick chat with us, he carried on, stating he was trying to make it into town that night so that he could do a glowworm cave tour in Lander the next day at 10AM.

We waved him off and promised to drive him to Dubois if he was still waiting when we arrived to the trailhead later tonight.

The hike up Down’s Mountain from the vast table lands not very far below

The walk to Downs Mountain was still long yet, and the terrain was strange, every hump and rock pile looked small for ages until suddenly they became mountains. Nor did distance make any sense.

The afternoon progressed slowly and with plenty of smoke. By the time we reached the base of Downs we didn’t have much more climbing to do, since we hadn't been below 12,000ft in many miles.

Ivey at the summit marker on Downs Mountain

Ivey and Lynn taking a selfie at the summit marker of Downs

We traversed several false summits before reaching 13,330ft and the true summit of Downs. This felt like the end of our adventure in many ways—I could barely believe we’d made it! In other ways we still felt leagues away from the Trail Lakes Trailhead where we’d parked my truck a week ago.

The bulk of our adventure had concluded but we still had to negotiate No Man’s Pass and Goat Flats, descend a ridge and find our exit trail.

The descent from Downs Mountain looking out over No Man’s Pass and Goat Flats

The landscape beyond Downs was stranger still and took on a spooky quality because of all the thick haze. Plateaus rose before us, their edges sharp and plummeting.

The scree field off the summit was unsettled and required our full attention, but it wasn’t nearly as unstable at the moraine fields around the glaciers. We kept up a steady clip even as our knees screamed to be done going downhill.

I nearly stepped into an abyss trying to locate No Man’s Pass, a narrow strip of land joining two large plateaus. When we made it onto Goat Flats, I took a bearing and found a rock pile miles in the distance that matched it, resolving to walk in a straight line directly towards it and not “wander” as Skurka discouraged us from doing in his guidebook. On such vast table lands it would be easy to walk senselessly in the wrong direction.

I locked onto my target and ratcheted up the pace; Lynn matched my stride, both of us eager to get lower and out of the smoke.

Goat Flats

Finding the ridge to follow down from Goat Flats proved to be the hardest bit of navigation I did all day. I thought I had it right several times, only to descend for a bit and realize we weren’t on track. We climbed up and over several fingerlike protrusions from the land mass until I was sure we had the right one.

I could almost see the trail cutting across the grassy landscape far below us and felt reassured by this. I rolled an ankle halfway down but kept walking. My ankles had been through the wringer on long trails and while rolling them sucked, it didn’t ever seem to slow me down.

Lynn on the Glacier Trail which would deliver us to Bomber Basin and ultimately Trail Lakes Trailhead and my truck

When our feet touched trail we both cheered and dropped our packs for a snack break. We’d done it! But of course we still had 8 miles to go. Those final miles we filled by swapping funny stories from high school, embarrassing interactions with boys and much talk of food.

Hiking in the dark feels insulating and in this case, it was a nice way to end a trip that had been so exposed for so long.

I’ve never completed a full thru-hike with a friend, end to end. I’ve had people join me for stretches and I’ve joined others, but this was the first time that a plan was hatched for a hike and seen all the way through. It means a lot that Lynn was willing to join me for what was a really challenging hike by any standard. I was so grateful for her company.

Ivey and Lynn, finishing at the Trail Lakes Trailhead in the dark